Ecological Fire Management in Kruger National Park

If fire has been present for a long time it may have to remain in order to maintain a site’s ecological integrity. Paradoxically, even as industrializing societies strive to eliminate open fire generally, they may have to retain or restore it on nature reserves” - Stephen Pyne

This project was born out of the idea to study three pillars of wildfires: history, ecology, and management, and their intersectionality in different countries. Essentially, there was a central question of how to infuse the ecological aspect of wildfires back into their management, and doing so in an increasingly uncertain world. A knowledge of landscape interaction developed by indigenous land users has dissolved within cumbersome bureaucratic agencies and a fast-paced society. Presently, many governments and communities are focused solely on themselves, unable or unwilling to prioritize the environment, let alone it’s more precarious mechanisms. Ecological wildfire is now mostly confined to language and empty mandates, its practice can only be found in small pockets.

My time with Parks Canada in Banff represents one of these positive examples, as it is the only Canadian entity I observed that is actively laying the fire down en mass for ecological aims. Other attempts for ecologically burning were taking place in Catalonia, but at a small parcel scale. The prescribed burning in Mafra Municipality (Portugal) is in a league of its own for its proximity of burning within highly developed infrastructure, however its focus is mostly hazard reduction as opposed to ecological. Similarly, there are significant burning processes and culture in KwaZulu-Natal, only the purposes of these burns are more oriented towards economic production (timber and grazing). The two areas (besides Banff) where this has not been the case are: Kruger National Park and Aboriginal management in Northern Australia (to be fair, I haven’t been to the Northern Territory yet, plan to visit has been postponed).

For most savanna ecosystems, fire is more important than rain. It is the impetus for life and biodiversity because many grasses are outcompeted in a few years by trees or shrubs. Fires may occur as regularly as every year, but many burn on cycles of 4-5 years, as lightening and human ignition during dry seasons play a crucial role. Without fire, many grazing or prey species will suffer as their foliage or the ability to watch for predator disappears under bush encroachment. Other bird species may lose valuable food sources as fires provide ample accessibility to insects, lizards, and beetles. Fire is a regular occurrence and many small creatures such as tortoises and hares can burrow under a passing front, and larger animals possess a simple comprehension just to move out of the way. If all of this seems tedious and elementary, it’s because it is and that is how it should be. Wildfire is not meant to be a necessarily exciting thing, it can be just as normal as a rain falling, an elephant walking through the bush, or a rocks rolling down a hill.

For Kruger National Park (KNP), it is impossible to ignore the importance of wildfire in maintaining the savanna’s ecosystem as well as the tourism that comes for the thriving megafauna that it supports. Simply driving around the park, it becomes abundantly clear that variance in vegetation cover is crucial for various fauna species. During my time in KNP, the approximate understanding that was provided was that species under 300 kg will exhibit strong preferences for areas burned annually, and species over 300 kg repeatedly select for areas with 5-10 years of vegetation growth. These preferences are based upon food availability and predator detection.

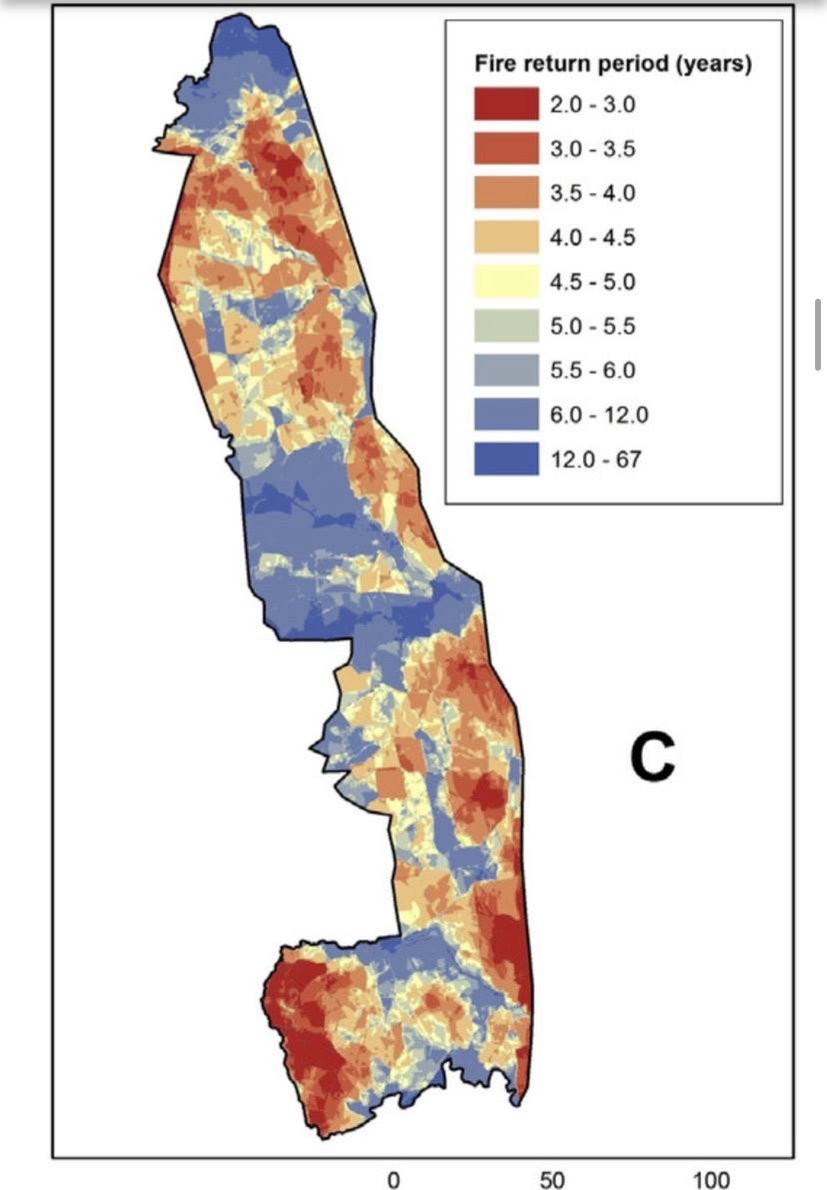

As with many national parks, KNP is afforded the mandate to focus extensively on the role of fire in its historical and ecological capacity. The absence of sprawling human development reduces civil protection pressures that are the primary handicap for most wildfire management agencies. Their status as a park allows for fire’s ecological role to be the priority, and with over 70 years of proactive fire management, KNP has developed some effective and innovative approaches to ecological wildfire implementation. Being the largest game reserve in Africa (7500 sq miles), the KNP extends across a wide geologic and rainfall gradient. This influences vegetation and subsequent fire regimes, and the KNP has taken the crucial step of developing a well of knowledge of fire history and extensive mapping. - In previous posts, I have written about the importance of the Sendai Framework, and the first step is Review. This is an excellent case study of an organization that is engaged in the Review process - Utilizing a fire scar history record (since 1941), combined with data from a fire effects project (since 1954 - more on this later), and lastly interlaced with the detailed geologic and rainfall research, the KNP has delineated the massive area into five distinct management types.

Through collaborative meetings between scientists and rangers, KNP created a zoning system that combines fire thresholds and the preferred ecological outcomes. This knowledge exchange and joint priority setting is crucial to allow for cross-communication of research and application. The product was the recognition of specific bio-geo zones with different science-based management actions for how to strategically apply fire. The creation of five distinct zones combines the severity and area targets of acceptable fire, as well as the desired landscape result:

- Zone 1 - regular prescribed burning. Fires should burn an area based upon previous two year’s precipitation. - Outcome should be maintenance of high quality grazing and healthy diversity of grass sward

- Zone 2 - mix of high severity burning (bush encroachment) and strategic, low-intensity burning (mosaic creation). Fires should burn about 33% of the area - Outcome should be to reduce bush encroachment.

- Zone 3 - reduce fire frequency and severity (reduce loss of important large trees); use strategic, low-intensity burning (create fuel breaks and mosaic) - Outcome should be the increase of tree saplings and maintenance of existing large trees.

- Zone 4 - no fire accepted - Outcome should be to maintain fuel breaks and protect infrastructure

- Zone 5 - no fire ecological objectives as fires rarely burn in these areas.

Zoning in wildfire management areas is not necessarily a groundbreaking concept, but it is super interesting to see it being done on a purely ecological basis.

The five distinct management zones are an approach based upon adaptive management and fire effects. “Adaptive management explicitly embraces uncertainty, recognizing that management may not deliver the desire results, that changes to these strategies may be required” (van Wilgen et al 2013).

When I was in Canada, one of the things that stood out to me was how personnel were frustrated at the lack of upkeep of strategy. Members of BCWS and AAF expressed to me that wildfire management plans were made, but updated maybe every 15 years to account for changing landscape conditions or to identify fluctuations in risk. In KNP, they update the burn plans every year. Part of this stark contrast can be attributed to different vegetation types and its status as a national park (where land-use is consistent), but still the difference is significant. KNP’s approach to it is straightforward and calculated as burn plans are based on the preceding two years precipitation. From this, wildfire management in KNP can dictate to the Sectional Rangers just how much area they need to burn. Simple fuels certainly add to the simple implementation, but its the mindset on updating and carrying out burn plans that is the real take away. How do other agencies that are struggling to get more fire on the landscape extract and adapt these mentalities and processes to be more ecologically oriented?

All of this information is coming from the time I was fortunate enough to get with KNP’s Fire Protection Officer, Navashni Govender (a trained entomologist, who has become a leader in proactive fire management). Between Navashni, Bob Connelly, and Brick Shields, the car was filled with interesting viewpoints on the current state of wildfire management. Needless to say, these three are huge proponents of ecological fire management and recognize that it is desperately lacking in our global approach to wildfires. Some other takeaways from my conversation with Navashni:

- When we think of “natural fire”, we must remember that man is natural part of the system and can not be systematically removed from the ecological process. Human ignition can be natural (USFS are you reading this?)

- Not burning is a management decision. By trying to avoid the liability of undertaking a prescribed burn, there are consequences.

- Anti-poaching is currently occupying most of the rangers’ attention, and wildfire management becomes secondary. A system of generalists (like KNPs section rangers) is beneficial because it taps into the holistic approach to environmental management, but it can be taxed as some priorities trump others.

- Navashni also took us on a tour of KNP’s Ecological Burn Project, which has been going on since 1954, and is a huge generator of knowledge for savanna fire ecology. There are 16 “strings” throughout the park, and each string contains various burn plots. Some of the plots are burned every year, while others every 2, 4, 8, 10, or never. This project has been extremely beneficial to understanding of regeneration of plant biodiversity, but is now focused on understanding fire-herbivory relationships. It adds inherent value to landscape management because it generates burning, data and practice, to remain within a government framework, what if other parks adopted similar fire ecology projects?

The approach to wildfire management in KNP is really important to learn from because it places value both on the certainty of the past and the uncertainty of the future. Across a large and heterogenous landscape, there is recognition that a “one-size-fit-all” approach cannot function, because the area has different fire histories and must have different ecological futures. Rather than try to mimic a historical fire regime, KNP has elected to learn as much as possible about the histories, allow for flexibility in the face of climatic uncertainty, and make management decisions that strive for identified ecological outcomes.