Engineering space shuttles and managing wildfires are not similar enterprises. One is highly calculated aerodynamics and the other is natural hazard mitigation. Despite being rooted in different disciplines of physics and ecology, there a parallel elements in the government organizations that exist in the oversight and application. Space and wildfire agencies must both utilize science-based decision making, and prioritize safety over efficiency. Both require strategic long term planning, as well as the ability to coordinate reactively. Systems of command and control are relied upon to ensure operational effectiveness and reduce risk to the greatest degree. Both types of work are dependent on motivated, experienced personnel to achieve objectives. Organizationally, both space and wildfire agencies may fall victim to similar institutional flaws.

In 2003, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration experienced its second incident of catastrophic failure within two decades. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) identified several glaring management discrepancies that were responsible for the loss of Challenger (1986), and then present once more for Columbia. The space shuttle’s technical malfunctions that transpired in operational situations were rooted in stagnant organizational culture and unidirectional communication.

The Investigation Board found that NASA promoted a culture of “bureaucratic accountability”, where strict adherence to hierarchy resulted in low-level engineers being intimidated to express concerns or propose ideas when problem-solving. The CAIB found that, “[NASA] emphasized chain of command, procedure, following the rules, and going by the book. While rules and procedures were essential for coordination, they had an unintended negative effect.” Additionally, the CAIB recognized that NASA maintained a stagnant, “perfect place” vision of their agency, rooted in the success of Apollo-era missions, that was slow to accept the new social contexts the agency existed within. Lastly, leadership within NASA engaged in “doublespeak”, using language and emphasizing priorities that were not supported by the actions and policies that were implemented. The CAIB found that NASA fundamentally failed to correct the systemic flaws that first lead to the Challenger destruction and were present in the Columbia dissolution, and concluded that NASA was not a “learning organization”.

Organizational culture pertains to the beliefs, values, and social norms that exist and define the functioning of an institution. It is the collective attitude of an organization and can be summarized as “the way we do things”. Organizational culture is a malleable mentality that is subject to environmental and political change. These value systems exist within an organization’s structure, which corresponds to the functional framework and actions taken by the entire group. Leadership plays a crucial role in crafting culture, but more importantly in the facilitation of appropriate alignment between culture and structure. Misalignment or incongruence between an organization’s culture and it’s actions can result in reduced efficiency and performance of an institution.

NASA’s culture of the Space Shuttle era draws parallels to existing attitudes within some Canadian wildfire management agencies. Largely focused on enhancing operational response and incident management, wildfire agencies have manifested strong and efficient command and control systems to maximize efficiency and coordination. These hierarchies, while vital on the fireline, exist within all sectors of wildfire management, including areas such as prevention, vegetation management, and others. Additionally, as environmental and global conditions are shifting at accelerating rates, wildfire agencies cultures are stagnant relying on successful histories of suppression. NASA’s “can-do” approach to technical obstacles was crafted under the highly political space race, and while it generated agency success during the Apollo era, compromised collaborative problem-solving during years of reduced public interest and funding. An inability to adapt agency structures to shifting environments placed increased pressures on personnel, as they were forced to do more with less. Organizational culture is heavily influenced by alterations in environmental and political landscapes. Lastly, NASA leadership emphasized safety in language, however their actions surrounding timelines and finances sent messages throughout the organization that efficiency was to be prioritized. WIldfire organizations all possess mandates regarding the importance of fire’s ecological role, but structural support for the achievement of these objectives is substantially less than language suggests.

Tasked with amorphous responsibilities pertaining to civil protection and natural resource management, wildfire agency personnel are attracted to the sector from a sense of public service, as well as environmental stewardship. From these motivational sources, and numerous others, there are values that emphasize the importance of both social and ecological roles of wildfire. Wildfire operations achieves belief-based incentives to address short-term social concerns surrounding wildfire, and is supported with significant structural support and funding. Environmental values within wildfire organizational cultures, however, are largely incongruent with current structures. This incongruence may manifest in the form of cognitive dissonance, or collective frustration and the inability to see one’s work as “good”.

Over the course of three month of interviews, including participation from over 50 AAF, BCWS, researchers, and municipal workers, several distinct narratives appeared. These narratives include:

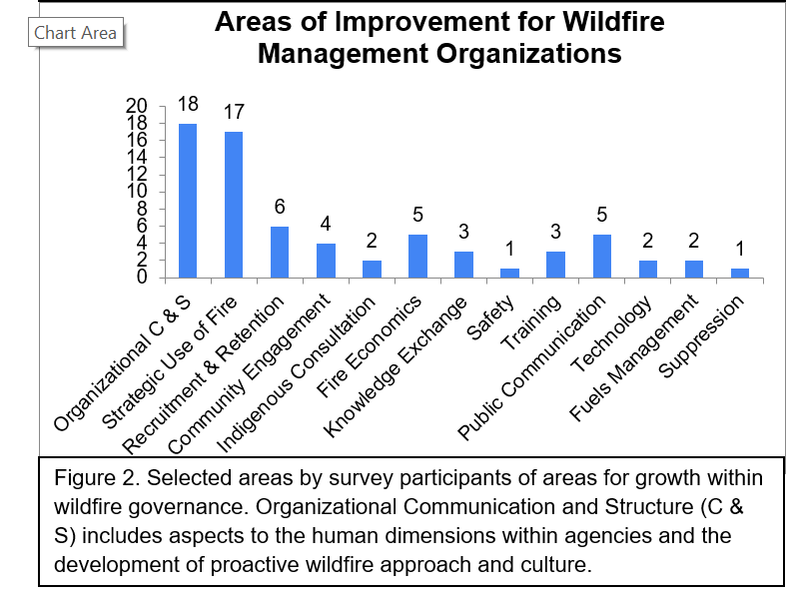

The importance of integrating historical fire regimes into wildfire management. 83% of individuals answered that it is imperative for holistic management. 17% of participants identified changing climate and environmental conditions as nullifying factors. 24% of individuals expressed that historical fire regimes have not been integrated into land management.The lack of homeowner accountability, and the future importance of homeowner participation in wildfire risk mitigation.The need for increasing the strategic use of fireAn imperative to increase support for other areas of wildfire management besides suppression operations. These areas chiefly pertain to mitigation activities such as prescribed fire and vegetation management, but other categories such as public engagement and fire ecology were also recognized. An acknowledgement that rising wildfire trends may be compounded by factors besides climate change, such as landscape interactions. This was identified as an area that must be communicated better to the public.

In their current capacity, wildfire organizations are not suited to adapt to rising wildfire trends. There must be structural changes to rise the level of innovation and adaptability.

The importance of the NASA case is that wildfire agencies must not fall into a similar trap; the creation and persistence of systemic organizational flaws that may contribute to increasing wildfire complexities. The CAIB pointed to three principle aspects within the NASA organization that may exist within wildfire organizations: a constant state of command and control, an inability to innovate new organizational visions when entering new contexts, and the impact of “doublespeak” from organizational leaders on personnel. One important distinction between the Challenger and Columbia incidents versus significant wildfire incidents, is that natural hazard events cannot assign responsibility for failure as distinctly as space shuttle malfunction. The management of ecosystems and their disturbance processes is not as exact as rocket science. However, significant wildfire seasons such as the 2017 and 2018 seasons in British Columbia, should and have prompted the reevaluation of agencies. At the very least, these types of significant wildfire incidents and seasons should instigate wildfire agencies to better understand the sentiments and beliefs of their personnel, at all levels.

Fire permeates all latitudes, and even at what feels like the bottom of the world, fire courses through the roots of South Africa’s ecosystems. Born on the fire continent, the fynbos ecosystem of Western Cape resembles many other Mediterranean-like climate biomes in its regenerative processes linked to fire. Literally meaning “fine leaf”, the fynbos resembles the arid adapted vegetation of southern California and it must burn in cycles of 12-15 years in order to achieve its desired fire severity. This natural cycle becomes complex when integrated with the valuable and expensive infrastructure we place within it, and we provide policies or negligence that shorten or lengthen this cycle. The mixture resembles those of other places, a landscape and human dimensions that are not in sync and thus experience occasional, volatile outbursts of friction.

My attraction to this place, in addition to its predisposition for fire, was the opportunity to relive my “lost” firefighting season of 2019. Due to my acceptance of the fellowship, I was unable to join my USFS brothers on the western slopes of the US, and so I opted to make form new fraternal bonds on the western slopes of SA. Joining the Nature Conservation Company (NCC) Type 1 Crew has been, by far, one of the most rewarding and challenging aspects of my year so far

The crew structure includes two distinct teams, “Alpha & Bravo” and “Charlie & Delta”, with their respective squads. In total, the Type 1 crew includes 20 individuals with fire experience ranging from 3 years to 20 years, and all with fitness levels equivalent to that of an endurance runner. Many are the product of Working on Fire (WoF), a government works project aimed at elevating members from low-opportunity communities. Most on the crew call the Eastern Cape of South Africa home, however Zambia, Burundi, and the DRC are all represented. Their stories and backgrounds range widely, however all are united in their love for fighting fire and their passion for one another. It is an incredibly tight group and it is a daily honour to have earned their trust and respect. Together we have fought many fires, with my current total for the season resting at 10 deployments. These deployments typically last 24 hours, and are riddled with glaring differences of the US experience.

Wildland firefighting is not recognized as a professional industry in the Western Cape, despite the massive risk that much of the region owns. The reason for this is that it is viewed as job for “unskilled labor” and the necessary knowledge of fire behaviour, ecology, mountain navigation, crew dynamics, and actual firefighting, is subsequently dismissed. The logistical aspects of firefighting in the US that we are so accustomed to: meals provided, rest time, water resupply, aerial resources, and others are absent here. The reality is that NCC outfits it’s “elite” units better than most as we deploy to the line with ration packs, and are therefore “self-sufficient for 24 hours”. Out in the field, the crew very much is on its own. There is no calling for aerial support, or for additional water, and I am afraid to ask the question about medevacs, mostly because I already know the answer. The country has been introduced to the Incident Command System, but it is still in its fledgling stage as the only noticeable aspects (viewed from the firefighter level) is the initial briefing that we receive upon arrival at an incident and the title “Incident Commander” and some of the other descending positions that are given in an ICS structure. I have noticed that positions such as “Logistics Chief” or “Safety Officer” are rarely present. Perhaps they are there, but I certainly have not seen them.

The national system of disaster management has made great strides to accommodate ICS, however it will be important to recognize where regional adaptations will need to be made. If there exist cultural or traditional histories that would make more sense to be integrated, then they would be integrated. For example, if Logistics in the American context is not feasible for SA, then those responsibilities must be probably integrated to other positions.

Fireline operations in South Africa brings a unique set of challenges that are fairly different to the US experience. In short, the physical act of firefighting is less extreme, but the logistical support absence adds an external challenging factor. With a constant direct attack approach, in which the firefighter is relatively close to their safety zone, there is reduced risk of an entrapment situation. The relatively rocky terrain and mixed vegetation age class offers opportunities to suppress or escape, if necessary. The packs and tools are significantly lighter, which allows for greater mobility, but are the trade-off for reduced water and food carrying capacity. Staying hydrated on the Western Cape fireline is exceedingly difficult and an operations area that must be focused on for improvement. On the line, crews must be self-sufficient to a higher degree, operating without significant communication (unless in highly residential areas) and without aircraft. Watching firefighters use a “beater” (stick with rubber flaps) to flap out bushes is really an organic way of stopping a fire. The only thing preventing the fire’s movement are the muscles and tendons of the firefighter standing in front of it. Compared to in the US, heavy machinery is often used (sometimes negligently) to create vast fuel breaks. The use of dozers, chainsaws, and even handline in the US can be more disturbing to the landscape than the actual high-intensity fire. Watching guys in SA put out lines of fire with nothing but grit and eachother is something to be observed.

South Africa is an experiment in humanity. The ideas, inventions, communities, art, governance that have arisen from the African continent’s edge are unique, and it was quite an experience to explore them in great detail. The prevalent histories, migration, cultural patterns, and economy challenged me to understand everyday. Trying to speak Xihosa in an old schoolhouse, or using Zulu to offer rides to grandmas from St. Bernand’s Mission, or questioning why I couldn’t understand the Afrikaaners on the Division. New ideas and approaches even trickle down to the legislation, and surprisingly a focus of my research. Concept models surrounding Fire Protection Associations and landowner accountability, or a national park fire ecology program that stretches back 75 years. South Africa made my head spin in a lot of ways.

With more severe wildfires on the horizon, there is a crucial need to develop fire adaptations for communities. This means that at-risk communities must accept the notion that fire is a part of their ecological landscape and they would be best suited to adapt themselves to coexist with the reoccurrence of fire. This approach is present within countless indigenous communities, recognition and synchrony with environmental mechanisms. In the 21st context, the achievement of this reality is dependent on high government standards (such as supportive policy) and willpower at the local level to carry out fire-related actions. Current strategies of all-inclusive government protection through wildfire suppression is neither cost-effective nor sustainable for hazard reduction. Even more importantly, in the case of many underdeveloped nations, the state is unable to function in a supportive capacity and offer a semblance of civil protection. In the near future, and arguably currently, many communities in developed countries are existing with the illusion of wildfire protection, and in developing countries there is no support or framework to address the issue.

What is community-based fire management? To me, it is the best (and most intensive) solution in improving human relationships with landscapes to alleviate wildfire threats. CBFM is based upon principles of localism, understanding and working closely in one’s area, but can be supported by global efforts. Principles of think global, act local.

One example of CBFM was my time in Nhlazuka, KZN:

The CBFM initiative that I visited in rural KwaZulu-Natal is a collaboration of international, state, and private entities. It includes support from players such as the U.S FireWise program, South Africa’s government program Working for Water, a non-profit Landworks, and the regional Richmond Fire Protection Association. To be honest, it was not entirely clear how all of those players fit together except that the training and standards came from FireWise (U.S), project coordination came from Landworks, and local supervision from Richmond FPA. From what I could tell, the only support from the South African state were the t-shirts, but I gathered that they may provide some funding (at the maximum). All of this is important because it reinforces the idea that even initiatives rooted in localism require criteria from higher levels of governance. Landworks oversees several of these CBFM projects across the country and is the driving body behind the success. However they are reliant on the international/state funding and local systems to implement accordingly.

The communities and nations of our global society are not operating in closed systems, and neither can our approaches to handling natural hazard.

Just a quick side note - South Africa’s Working for Water (WfW) program is actually really novel and interesting, even if it is not always the best functioning system. Consistent with South Africa’s innovative (and unenforceable) Alien Clearing Act, WfW addresses environmental concerns surrounding alien species and natural resource loss. WfW functions as an expanded public works program (EPWP) to employ and benefit economically disadvantaged communities, and to remove alien vegetation (primarily Australian species) to reduce fire risk and increase groundwater accumulation. I cannot think of a single piece of legislation or government social program in the US that addresses alien species, or their connection to water loss.

The local implementation of CBFM is reliant on the governance systems that I have previously mentioned, but in Nhlazuka it also includes are more impactful framework, the local tribal government. The Umkomazi river area falls within traditional land of King Shaka of the Zulu’s. In the Nhlazuka areas, there are approximately 10,000 people that are divided into 13 sections, each under the leadership of a Zulu Headman. The 13 Headmen form the Nhlazuka Council, and the buy-in from each council member is essential to the success and legitimacy of the FireWise CBFM program. Through the program, each of the 13 areas has a designated FireWise team of 10 individuals. The FireWise committee for that area, made up of the Headman and others, identify project sites for their team and also nominate upstanding community members to be considered for team selection. The project sites are typically waterways that have become overgrown with alien vegetation (such as Black Wattle, Cyringa, Bugweed, Castor Oil plant, etc), but they may also be areas identified for grazing restoration or high fire risk areas. Personnel grooming and selection from the committee is also influential as it puts forward individuals with strong positive qualities. There are extremely few economic opportunities in these rural areas so competition for a place on a FireWise team is prevalent.

The FireWise teams themselves focus solely on wildfire prevention - fuels management and raising community awareness - and leave technical fire use and firefighting to the Working on Fire teams. While they are trained in understanding fire behavior, it is primarily to understand the importance of reducing alien fuel loads and defensible space. However, the closest Working on Fire teams to Nhlazuka are 20 miles away, so the FireWise teams are the local authority on wildfire.

Here are some more thoughts on working in Nhlazuka, but more from an experiential point of view:

My many years playing racing arcade games could not have prepared me better for driving the roads in Zululand. Except in midst of all those lights and tickets, I was stationary and not elevating my heart rate to flow-like conditions. The Zululand roads are an experience to be had, and me with my NPS 3000 single cab saw it all: Cows, lightening, armies of school children, snakebites, drunks, and an onslaught of potholes. I loved every minute of it. In a way, me and my “bakkie” became a short-term staple of the Nhlazuka Valley. Everyone stared at us when we drove past, but after a while the stares were accompanied with waves. It felt good when I would pick up hitchers and they would know exactly where I was from and what I was doing in the valley. It felt like acceptance. I wish it could have lasted longer, but my bakkie and I had roads to travel and promises to keep.

In my opinion, one of the best outcomes of focusing so much of fire research during this travel year is the sense of purpose when engaging in communities and landscapes. Little of my time has been spent as a conventional tourist, and most times I am operating with a somewhat legitimate rationale for being there.