Raise the Minimum

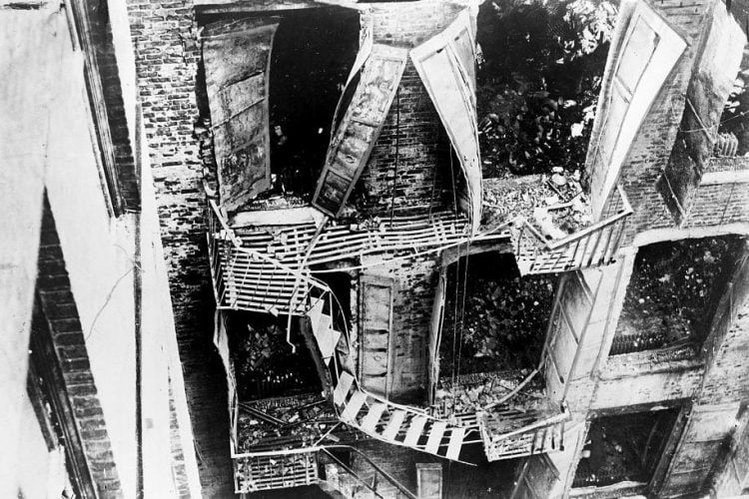

On March 25, 1911, a fire in a New York City garment factory broke out due to an unextinguished cigarette in a fabric waste bin. At the time there was little legislation surrounding workplace- and fire-safety and as a result, the factory was loaded with flammable fabric (fuel) and the few possibilities for egress were locked or inadequate, there were no alarms or extinguishers, and no plan. 146 people perished in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory because they were unable to escape the conflagration, the only fire escape buckled under the weight of so many people and many fell to their deaths. Without legislation, the factory’s management had been free to follow minimal codes and bylaws such as reduced fire escapes, excessive flammable material, and no coordinated safety plan for the workers to follow. The response to the travesty was sweeping legislation aimed at ensuring such an industrial catastrophe could not reoccur. With momentum from the incident, the State of New York passed sixty laws designated to standardize the practice of building ingress and egress, the use of fire sprinklers, alarms, and extinguishers, and fireproofing requirements; these laws radiated to other states and the American Society of Safety Professionals was instituted. In a wildfire context, we have reached our Triangle Shirtwaist Factory moment, but we are missing the window to use the momentum.

In 2018, California experienced its first Triangle moment as the year-long season brought 103 wildfire caused deaths, over $3.5 billion in costs, and the destruction of approximately 23,000 structures. With 1 in 4 Californians living in high fire risk environments, these numbers can be expected to rise. The 2018 season created massive momentum and anxiety for everyone, however in California the focus has been on the utility companies to enact change and this completely deviates from the ability to change our wildfire fate. My birth State needs to look to history to identify salvation pathways to avoid the continuation of the downward, crisis spiral.

Just as in 1911, when sprinklers, alarms, extinguishers, and knowledge about emergency exits and flammable material existed in society, people died in mass because legislation did not exist to ensure their use. As stated in many of my interviews, “people, and specifically those who aim to enhance a bottom line such as developers or builders, will always follow minimum code” or put another way, “without legislation, politics and [economic] return will reign”. The technologies and knowledge about how to protect communities from wildfires exists today, wildfire management agencies are literally screaming their objectives for community protection. It just so happens that those same objectives are remarkably similar to the ones set after the outcome of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire: reduce flammable fuels, identify adequate areas for ingress (of firefighters) and egress (for civilians), use sprinklers and alarm technologies, and have a coordinated safety plan that everyone can understand. Today highly impactful wildfire incidents in the U.S and Canada have provided momentum and political pressures to enact change, this desire for change however tries to achieve the objective through indirect methods.

While California is busy scrambling to figure out the absolute mess it has created for itself and media outlets ascribe blame to soulless utilities, other governments such as Alberta and British Columbia have begun down other pathways. But first, a brief description for why AB and BC are concerned about wildfires: For British Columbia, back-to-back record breaking seasons in 2017 and 2018 burned over 1.2 million hectares (approx 3 million acres) and 1.3 million hectares (3.2 million acres), cost $650 million and $615 million, and evacuated a cumulative 71,000 people. For Alberta: in 2016 the Horse River Fire lead to the death of two people (but had the potential for significantly more), destroyed 2400 buildings, and cost about $10 billion. This 2019 wildfire season has been a record breaking year for Alberta as over 800,000 ha (2 million acres) have burned, lead to the evacuation of 10,000 people in May alone, and severed a key economic railway that supports northern communities and economic activities:

As a result, both Alberta and British Columbia are especially concerned about the wildfire risk. Interest and anxiety persists at all levels: individual homeowners, communities, industry, wildfire experts, and politicians. This interest has weight and is leading to action; budgets for FireSmart (the national program for reducing threats to the wildland-urban interface) are booming, and BC has altered its mandates to place a significantly higher emphasis on wildfire prevention. These steps are crucial in their own ways, but their abilities for implementing change are extremely limited without legislative mandates.

When it comes to protecting communities in Canada, FireSmart is the national program initiated to distribute knowledge and criteria for preventing a wildfire from burning subdivisions and individual properties. There are a myriad of nuances and complications that challenge the successful and widespread implementation of this criteria, but FireSmart is the body behind the standards. I met with the national coordinator as well as the provincial team (Alberta) responsible for the 7 disciplines of FireSmart: emergency management planning, vegetation management, education, development, legislation, interagency cooperation, and local land-use planning. I could really go on and on about FireSmart, its successes, failures, and areas for improvement, but overall the program is an amazing one with a virtuous mission. It seeks to educate the public about wildfire risks, the need for homeowners to reduce the susceptibility of their homes to direct flames as well as embers, facilitates large-scale vegetation management to protect community and industry values, helps provide training to structural firefighters on the challenges of wildfires, participates in schools to boost awareness, and overall goes above and beyond to try and get people to pay attention and protect themselves. FireSmart is not the problem, getting other entities to follow through on FireSmart objectives is the problem. The program is reliant on buy-in from individuals, municipalities, industry, legislators, and developers to adopt a “wildfire lens” to produce effective, meaningful action. In its quest to protect human life and property, the greatest hurdle for FireSmart is human will.

Returning back to the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, the absence of human will paved the way for the tragedy as well. Because legislation did not require alarms, extinguishers, or sprinklers, it would have required additional will for the factory to provide those. Instead they diverted and followed the minimum. The City of New York exemplified poor willpower when they permitted the factory to only build one fire exit, even though they had advised more be built. Willpower would have been required to clear the floors of the scraps and rolls of flammable fabric that covered the factory, but instead they sat and accumulated. Reliance on willpower contributed to the death of these 146 people. In an investigation following the incident, NYC identified over 200 other factories that had remarkably similar conditions. How many communities look like Paradise, CA?

The Factory, to me, represents hundreds of communities in the U.S, Canada, and probably elsewhere. To date, we have built, lived, and operated in wildfire environments and have taken into account NONE of the implications. Our homes and businesses are surrounded by flammable vegetation (even more flammable than fabric in some cases), and we lack the will power to clean it up, and so it accumulates. We allow many of drive-ways and roads (ingress for firefighters and egress for everyone else) to become narrow for aesthetic or commercial reasons, and we don’t review and spread awareness about safety plans or instill technologies to aid us. We permit development to occur without concern for natural hazard, in many cases homes are built with flammable materials. In the aftermath of the Horse River Fire in Alberta and also the Tubbs Fire in California, homes are rebuilt in the same locations with the same materials that lead to their combustion. The survivors of 1911 would be ashamed of us because we still hold onto hope that human willpower can shift. When will we learn to enact meaningful legislation to remove the willpower element, and get on with change? How many more communities need to be incinerated? It may be time to stop looking at the utility companies, or questioning what tactics wildfire agencies could have used. It is time to look at our government leaders - from homeowner associations to federal bodies - and ask for an elevation of the minimum for community protection.

Thanks for reading, here’s a Grizzly Bear: